Turning Around Schools: 3 Ways for Schools to Stop Struggling

Author: Andy Cindrich

March 20, 2019

Turning around schools is no easy feat.

Schools across America are dealing with unprecedented challenges, including inadequate funding, school safety concerns, tremendous pressure to improve academic outcomes, discipline issues, equity, resilience, and absenteeism, to name a few. While overall standardized test scores are improving nationwide in the U.S., family income and racial gaps are widening. Many schools are struggling. And as we mentioned before, turning around schools is no easy feat. It requires tenacity, accountability, and trust.

Turning Around Schools & Trust

Turnaround schools need leaders—leaders who know how to engage teachers, students, and staff to bring their very best to school every day, week after week, quarter after quarter, and year after year. An engaged individual can answer “YES!” to this question: “Are you a valued member of a winning team, doing work that matters, with people you trust?”

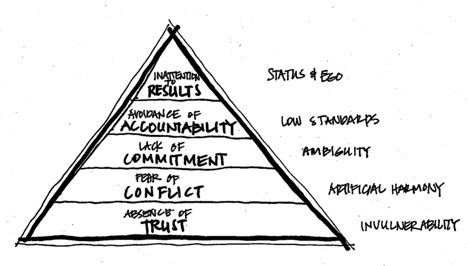

So how do you create the conditions for engagement? It starts with trust—the confidence people have in credible leaders and their vision for the future of the school. The absence of trust is the foundation of Patrick Lencioni’s The Five Dysfunctions of a Team.

Credible leaders have the integrity to make hard choices in the face of opposition; they are humble enough to admit that they may not have all the right answers; they work to help everyone win; they matter to the effort with talents, skills, and knowledge combined with a can-do attitude and a style that is easy to do business with. They also have a growth mindset that, if they don’t yet have a track record of successful turnarounds, allows them to say, “I haven’t done it yet!”

When credible leaders work with stakeholders to craft and then communicate a shared vision for the school, then students, teachers, staff, and the community alike believe. Stripped of suspicions, they quickly get aligned and begin to see themselves as a valued part of an exciting future.

Identify Critical Performance Gaps

Educators that are involved in turning around schools can stimulate progress toward that vision and help people know what winning looks like, leaders must identify the critical performance gaps that have to be closed to move the school forward. For many elementary schools, the most critical measures of success include the percentage of students reading at grade level by the end of the third grade and math scores—and a year’s worth of academic growth in those two areas every year.

Once leaders and teachers agree on the critical outcomes they need to focus on, teachers then need to identify the behaviors, activities, and circumstances that produce those outcomes. In the book Influencer, the authors detail how to find vital behaviors by:

- Identifying high-leverage behaviors that lead to rapid and profound change

- Applying strategies for changing both thoughts and actions

- Marshal six sources of influence to make change inevitable

With focused objectives and vital behaviors in place, the school is ready to start playing to win. Two human performance-enhancing mechanisms will help scoreboards and accountability. Simple scoreboards let administrators, teachers, and students know at a glance how they are doing. Like scoreboards in athletics, scoreboards in school hallways, classrooms, and student notebooks create energy from the fans, guide administrators and teachers in the plays they call and motivate students to step up their efforts and innovate to succeed.

Accountability

In her book Confidence: How Winning Streaks and Losing Streaks Begin and End, Rosabeth Moss Kanter wrote, “Every winning streak begins when leaders create a foundation for confidence.” They do this by setting the three cornerstones of confidence: accountability, collaboration, and initiative. Leaders interested in turning around a school set those cornerstones when they combine the access everyone gets to the data from scoreboards with a weekly rhythm of accountability.

Each week, administrators meet to make specific commitments about what they will do to support improvement. They work “on” the system to help teachers and students execute the goals. Teachers (often in collaborative teacher-based teams or departments) meet in short, focused meetings I like to call “Visine® Meetings” to make commitments to each other about what they will do to “get the red out” (an advertising tagline for Visine eyedrops) of their classroom scoreboards. Students meet in small work teams or Accountability Buddy groups to make commitments about what they will do in the coming week to improve their scores on assignments and assessments. These commitments reflect the individual initiative of administrators, teachers, students, and staff. To complete the accountability process, the following week, as part of a repeating rhythm, these same groups meet to report to each other on their commitments and, based on the new scoreboard data, make new commitments for the coming week to continue progress or address shortfalls. As Rosabeth Moss Kanter wrote in a short HBR column, “Teams that are immersed in a culture of accountability, collaboration, and initiative are more likely to believe that they can weather any storm. Self-confidence, combined with confidence in one another and in the organization, motivates winners to make the extra push that can provide the margin of victory.”

There may be no more important work to do than turning around a school that’s been in a long academic and/or cultural slump. This work is not for the impatient or faint of heart, and while the circumstances in turnaround schools are very difficult, I like what George Bernard Shaw wrote: “The people who get on in this world are people who get up and look for the circumstances they want, and if they can’t find them, make them.”