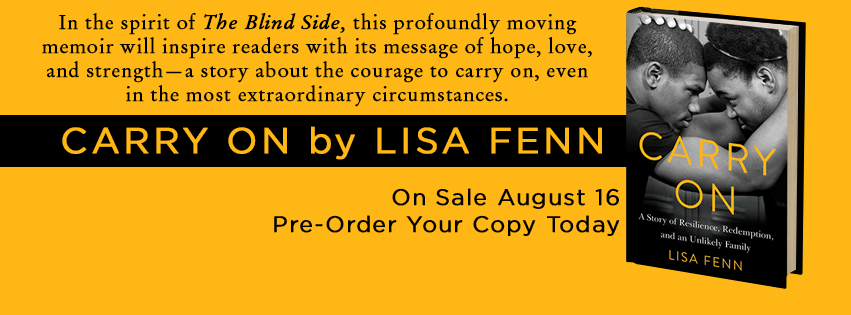

‘Carry On’: A Story of an Unlikely Family

Author: Carissa Logan

August 10, 2016

This is a guest post written by Lisa Fenn, three-time winner of the Edward R. Murrow Award, a six-time Emmy Award-winning feature producer with ESPN for 13 years, and Author.

At the core of The Leader in Me philosophy is the belief that every student is gifted with special abilities; that every child can make meaningful contributions in the world; that educators can take a stand for greatness and love their children into leaders.

But once you leave this blog and return to your classrooms, you will inevitably encounter a student who makes you wonder if it is ever just too late. Has life ever taken so much of a toll on a child that the effects cannot be reversed? What if you can’t find the child’s gift? What if the search is uncomfortable? Is there a point at which it’s okay to give up, or can love really conquer all?

I asked all of those questions in 2009 when I met Dartanyon Crockett and Leroy Sutton, high school seniors at the time, in Cleveland, Ohio. And in the seven years that followed, as the three of us grew closer, we learned some surprising answers. This is our story.

“Why did you stay?”

He asked me, unprompted, as we waited quietly for the light to turn green. My heart revved. I thought he knew.

“I love you,” I answered.

“That’s what I thought you’d say,” he replied. “But why did you stay and do everything you did for us?”

The answer to Dartanyon Crockett’s second question was not as tidy as the first. Because life can be a knotted mess and, sometimes, love is not enough.

Dartanyon and his best friend, Leroy Sutton, grabbed hold of my heart seven years ago. As an ESPN television features producer at the time, I traveled the country, chronicling human-interest stories against the backdrop of sports. I covered Tom Brady and Derek Jeter as well as terminally ill Little Leaguers and disabled amateurs, all who imprinted their own special brand of heroics onto this world. How privileged I was to be invited into their private pains and sacred celebrations.

But what I found on the wrestling mats at Cleveland’s Lincoln-West High School in 2009 caused my spirit to sink and soar, all in the same moment.

Dartanyon was Lincoln’s best and strongest talent. He was 5 feet 7 inches with muscles bunched like walnuts and a winner in multiple weight classes. He was also a transient, subsisting on the soggy mozzarella sticks and bruised apples served in cafeteria lunches. His mother died of an aneurysm when he was eight years young, at which point his father collected him and took him to live in an East Cleveland crack house. Where exactly it was Dartanyon could not say because Dartanyon is legally blind. Born with optic neuropathy, a condition that causes vision loss, he struggles to make out the facial features of a person sitting a few feet away.

Perched atop Dartanyon’s back was teammate Leroy Sutton. He rode around up there because he had no legs, and the school gymnasium lacked an elevator. And because when he was 11 years young, he was hit by a train. A freight train. Though the paramedics saved his life, they could not save his entire body. His left leg was amputated below the knee, his right leg below the hip. His mother, ravaged by guilt, slipped into drug use and disappeared for stretches of time, leaving Leroy alone to care for his younger sister. His father spent much of Leroy’s youth in jail. The “why” questions haunted Leroy, but he learned to mask their torment with a quick smile.

The one with no legs being carried by the one who could not see. At first, I stayed because I simply could not look away.

In addition to being intense practice partners, Dartanyon and Leroy shared a handful of classes, always sitting side-by-side. Dartanyon would get up to sharpen Leroy’s pencils; Leroy ensured Dartanyon could read small print. Yet, each time I allowed myself to revel in their tenderness, they reverted to teenage humor with a twist that only they could share.

“Leroy, if you left home, would you be considered a runaway or a rollaway?” Dartanyon asked.

“If you were looking for me, I’d just be gone!” Leroy replied.

Afterward, they barreled down the halls together, their echoing laughter the brightest light in that dreary place. Dartanyon kept a hand on Leroy’s wheelchair, in part as a guide for himself but also as a protector, a brother, for Leroy. Their teachers remarked to me that they were “some of the good ones.”

Their cheerfulness stood out in a school marked by irreverent students and sunken teachers. Seas of Black and Latino teens poured through the metal detectors each morning, many stopped for pat-downs. One boy wearing no coat on a blistery March morning was turned away, the security guard informing him that he had been expelled the week prior. There was an arrest in the hallway after 10th period. Books were handed out and locked back up after each class. Less than 40 percent would ever graduate; untold numbers were left pregnant. No one was thinking “win-win.” Yet Dartanyon and Leroy moved throughout the chaos with grace, with a refusal to have their hope tainted. “Destined for Greatness,” Dartanyon scribbled on his pages throughout the day. They seemed oblivious to the negative limitations on their lives.

Producing the 2009 story “Carry On” challenged me in new ways. Instead of telling the story of an individual accomplishment or a remarkable moment, this conveyed a friendship. And in order for the nuances of a friendship to unfold naturally on camera, I needed to become a part of it. Calling out, “Be funny on the count of three,” or “Now convey warmth on this take,” is artificial. This story required me to be in on the jokes and move fluidly with the characters.

I found this difficult at first, because I grew up on the other side of Cleveland. The White side. Though I was raised just 8 miles west of Lincoln, my parents scrounged up the money for private school to protect me from the public schools and “those people.” Through all of their summer yard sales and side jobs, I silently wondered what was so bad about the people “over there” to prompt their determination. Now I realized their internal discomfort was probably akin to the visible uneasiness I wore standing in Lincoln’s halls. Small, shy, blonde, and studious, I would not have survived a week.

But Dartanyon and Leroy eased me in graciously. I tagged along to their classes, to their practices, and on team bus rides. They taught me their lingo and poked fun when I tried to use it. Leroy and Dartanyon shared the details of their lives cautiously, testing what I could handle—to see if I would leave. They had never before had a safe place in which to tell their stories, or a safe person to whom to tell those stories. After years of emotional abandonment, both boys began to believe that, perhaps, I genuinely cared.

I stayed because I would not be next on the list of people who walked out and over their trust.

After the wrestling season, Dartanyon and Leroy competed in powerlifting. Leroy held the Ohio state record in bench press, Dartanyon in deadlift. Immediately following his conference powerlifting-championship win in April 2009, Dartanyon discovered that all of his belongings had been taken from the bleachers. Stolen along with them was his right to celebrate. Every victory in his life was ripped from him before he could even taste it.

That week, I drove Dartanyon around town to replace his lost items. A new bus pass. Another cell phone. A trip to the Social Security office for a state ID, which required a birth certificate, which had been confiscated during his dad’s last eviction. His was a cruel world, even for a sighted person. How he endured it in shadows baffled me. I paid for all of his items, arguably crossing a journalistic line. But this was quickly becoming less about a story and all about soothing the suffering. Dartanyon later told me it was during those errands that he grew convinced God had placed me into his life for reasons beyond television—that no one else would have taken the time and money to help him in those ways.

Soon thereafter, I traveled to Akron to film Leroy’s childhood neighborhood. This required a police escort. “Welcome to Laird Street,” the officer said smugly. “We call it ‘Laird Country,’ because once they’re born onto Laird, they never leave. They just move from house to house, up and down, following those drugs.” Shadowy men loomed on the dilapidated porches of each home, while the streets were filled with children who should have been in school. “Your guy must have been real lucky to get out,” the officer remarked.

I stayed because my heart was too heavy for my legs to walk away. Dark clouds hung over every turn of Leroy and Dartanyon’s, and I found myself pleading with the heavens to end this madness.

That summer, I feverishly edited “Carry On,” praying that just one viewer would be moved to help these boys in meaningful ways. But instead, following its airings, a legion emerged. From Ipswich to Idaho, men and women, young and old wrote to offer money and share personal accounts of how this extraordinary friendship shook their souls awake. Dartanyon and Leroy’s plights were no longer invisible. I fell to my kitchen floor and wept.

In the months that followed, I personally responded to nearly a thousand emails, not wanting to miss out on a blessing. Round the clock I harnessed donations, vetted speaking invitations, deciphered financial-aid forms, coordinated college visits, and ensured Dartanyon and Leroy were finally fed on a daily basis. Each time I shared exciting new developments with them, Dartanyon gushed with thank-yous and hugs, broad grins, and relieved exhales. But Leroy’s appearance of apathy never budged. “Leroy, if at any point you don’t want this, you need to speak up,” I said. “I’m not in this to inflict my desires on you.”

In the months that followed, I personally responded to nearly a thousand emails, not wanting to miss out on a blessing. Round the clock I harnessed donations, vetted speaking invitations, deciphered financial-aid forms, coordinated college visits, and ensured Dartanyon and Leroy were finally fed on a daily basis. Each time I shared exciting new developments with them, Dartanyon gushed with thank-yous and hugs, broad grins, and relieved exhales. But Leroy’s appearance of apathy never budged. “Leroy, if at any point you don’t want this, you need to speak up,” I said. “I’m not in this to inflict my desires on you.”

“No, it’s all good,” he said.

“But usually, when it’s ‘all good,’ people smile or say something,” I said. “Each time I call you with good news, you are so quiet. I’m not even sure you’re on the line.”

“No one’s ever called me with good news before,” he said. “I don’t know what I’m supposed to say.”

He once told me that Christmas was his least favorite holiday because his mom wrapped up Bazooka bubble gum and toys from around the house, hoping he wouldn’t notice. Having never known pleasure, he had not developed the language to respond to it.

“But I am happy inside,” he added. “My dreams might come true.”

I stayed because I vowed right then to fill Leroy’s life with a thousand good things until he simply burst with joy.

In November 2009, Leroy moved to Arizona to study video-game design at Collins College. Getting through college was a struggle, but he did it. He was the first in his family to graduate from high school, and in 2013, he was the first to receive a college diploma. Dartanyon and I were in the front row, listening as the sound of this cycle of poverty shattered.

Dartanyon received his life-changing offer from the United States Olympic Committee in March 2010. Recognizing his natural athletic abilities, coaches invited him to live at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs to learn the Paralympic sport of blind judo. This was akin to a winning lottery ticket: housing, competition, mentors, school, health care and, as he proudly showed me on a visit to Colorado, his first bed.

“Top judo athletes begin training at a very young age,” his coach confided. “We don’t know that Dartanyon can make up the years by the 2016 Games.” But a little doubt was all Dartanyon needed to work his fingers into calluses and his heart into that of a champion. He unexpectedly earned a spot on the 2012 Paralympic team to London. Leroy and I celebrated in the front row as the bronze medal was draped around Dartanyon’s neck. Once forgotten by the world, Dartanyon stood on top of it.

“Things like this don’t happen to kids like us,” he cried on that unimaginable night, his face beaming bronze, his tears soaking into my shoulder.

And he is right. Blind and legless kids from the ghettos don’t get college educations and shiny accolades, but they should. And that is why I stayed. Because hope and love and rejoicing and redemption can happen to kids like them. And people like me, people from the “other side,” who are in positions of strength, should be actively meeting their needs.

And he is right. Blind and legless kids from the ghettos don’t get college educations and shiny accolades, but they should. And that is why I stayed. Because hope and love and rejoicing and redemption can happen to kids like them. And people like me, people from the “other side,” who are in positions of strength, should be actively meeting their needs.

I have spent thousands of hours removing obstacles from the paths of Leroy and Dartanyon’s dreams, and reprogramming the mindsets of poverty: how to pay a bill, plan ahead, have conversations with those in authority, utilize community resources, and develop healthy relationships. Of equal importance, they learned to verbalize their traumas—to talk about them rather than shroud them in shame. Talking became like oxygen. It gave them life. And as they came to understand their histories, they grew less likely to repeat them.

Leroy and Dartanyon’s pathway to self-sufficiency required more than handing them opportunities. The journey required constant support over many years. It required a love free of strings and full of patience. And through it all, we grew into an unlikely family of our own. We carried on.

When applying to college in 2009, Dartanyon wrote in my name as his emergency contact. Soon after, I received a call from the office administrator. “I just thought you should know what Dartanyon wrote on his form,” she said, somewhat undone. “Next to your name, on the release, is a space that says ‘Relationship to Student.’ Dartanyon wrote ‘Guardian Angel.’”

I stayed because we get only one life, and we don’t truly live it until we give it away.

I stayed because we can change the world only when we enter into another’s world.

I stayed because I love you.

Lisa Fenn is a three-time winner of the Edward R. Murrow Award and a six-time Emmy Award-winning feature producer with ESPN for 13 years, Lisa has interviewed every big name in sports. Today she is a sought-after public presenter, speaking on leadership, poverty, and transracial adoption, in addition to her faith and its relevance in both her media career and her daily life. Lisa received her BS in communications from Cornell University. Her work has been featured on ESPN, Good Morning America, and World News Tonight. Lisa resides in Boston with her husband and two young children.

Share Article on

Tags: Carry On book, community engagement, leadership, student empowerment, student motivation, student potential, teaching leadership, The Leader in Me, what we're reading